|

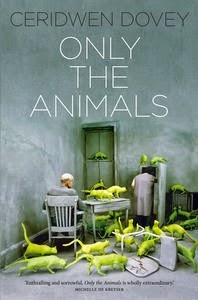

| cover credit: Finishing Line Press |

The Buried Return by Christine Stroud

Finishing Line Press (2014)

Reviewed by Mindy Kronenberg

Christine Stroud’s debut chapbook is a collection of poems that are each a cautionary tale. These disturbing but determined narratives face the harrowing realities of love (both carnal and familial), loss, and random rites of passage emerging from the domestic and feral realms. The adolescent bravado that begins this journey evolves into adult indignation and self-recognition with every vignette, and raw emotions are crafted with literary precision.

The first poem, “I Threw Your Shoes into the River,” is a provocative start. The poet claims not to regret the gesture (for an unnamed victim). Yet, in this passage, there remains a searing image of summer shoes thrown defiantly and disappearing from view:

… But I

stood at the end of the pier

and watched your Day-Glo orange

flip flops float down the White Oak

until they were nothing

but a burnt smear on the water.

Many of the poems in The Buried Return are encounters meant to haunt the reader, pull us out of a comfort zone that so many poets struggle to preserve. The way Stroud summons empathy and trepidation from visceral (and sometimes alarming) details recalls Theodore Roethke’s and Sharon Olds’s rending of personal violence into eloquent verse—the language sublimely releasing events that make us wince. The brutality of ignorance and bigotry and the complicated injustice of victimization is rendered in “Farmville High,” where a lesbian student is physically attacked by two boys after school. The tension begins before the violence, as her attackers position themselves (“One at each end of the hall. / Even before they yelled / dyke, you understood.”). The carnage that follows leaves us speechless:

…

They shattered you

under long fluorescent

bulbs running parallel

to the cobalt blue lockers.

Those lights always

too clear, too white.

…In silence, the doctors

rearranged you, wrenching bones,

wiring your mouth shut.

Lessons of loss and mortality are poignantly demonstrated in two poems, “Knowing” and “On the Way Home from a Bar in Portland,” which take place respectively in childhood and adulthood. Focusing on a hunt for a lost cat and an encounter of another, horribly wounded, each deals with the uncomfortable urges of hope and bravery, survival and merciful death. In the first poem, configured as a prose narrative, the discovery disappoints: “I find him. Curled up like a roly poly, his mouth hanging open, blood on his / teeth. His tiger-striped fur looks soft and I bend down to stroke him. Dad / grabs my hand, No he could have diseases. …” In the second poem, a more formally constructed narrative that is built on self-doubt and ending suffering, the poet follows a “tar trail of blood” to a hedge where the animal appears:

… He was a pair of torn black pantyhose,

leaking thick pink mucus. I should’ve gone home. …

…

I envisioned snapping his neck bone.

Instead I scratched him between the ears, stilled

by his sticky, short breath. I got up, walked home.

There are several poems on family with their own brand of spirited, celebratory dynamic, as when a walk in a graveyard becomes a bonding session for mother and daughter (“Graves We’ve Shared”), a father-daughter fishing expedition that’s a lesson on “the patience of stillness” (“Fishers”), and a hammock nap recreating the loving tension between the practical grandmother and rebellious sprite (“Grandmother”). A complicated chasm between revelry and sobriety exists in poems on friends and lovers (particularly in four “Relapse Suites”), and even the most raucous scenes contain imagery and detail with a peculiar beauty—“as bullets fell into the snow / like awful inverted stars…” (“Relapse Suite, Ashville”) and “It was so cold in your room / the door handle sparkled / with frost.” (“Relapse Suite, Pittsburgh”).

The Buried Return is by turns tragic and tender, wild and disciplined. Stroud unearths what we fear and desire, and reminds us how poetry can haunt both our conscience and consciousness, chronicling and shaping the lives we choose for ourselves.